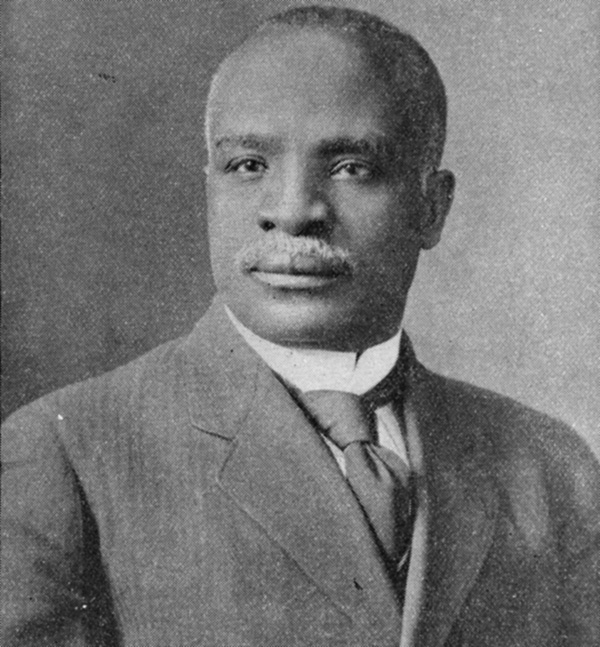

Kelly Miller: mathematician, intellectual, and political activist. Miller was born on July 18, 1863, in Winnsboro, South Carolina to Kelly and Elizabeth Miller. Like many African Americans who took advantage of increased educational opportunities after the civil war, Miller attended Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1886. During his time at Howard University, he served as a clerk in the US Pensions Office.

In 1887, Miller became the first graduate student at Johns Hopkins University where he studied mathematics and physics. After an increase in tuition, Miller was forced to leave Johns Hopkins in 1889 without completing his graduate work. He continued his studies as a student of Captain Edgar Frisby, an English mathematician at the US Naval Observatory, and briefly taught mathematics at M Street High School in Washington before being hired by Howard University as a professor of mathematics.

Miller taught mathematics at Howard for the next five years. In 1897, he helped found the first organization for black intellectuals known as the American Negro Academy. He also enrolled in Howard University for graduate school, earning his Master of Arts in 1901 and an LL.B (Bachelor of Law) from Howard University Law School in 1903.

Like many of the 20th-Century Black American intellectuals, Miller believed that the developing social sciences would be useful in assessing the experiences of Black Americans and in charting a course for their future advancement. He helped organize Howard’s sociology department during the 1890s and served as a professor of sociology from 1895 to 1934. Miller’s interest in the plight of African Americans encouraged him to help W.E.B. DuBois in editing the Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In addition, Miller crafted numerous lectures and pamphlets that examined the racial experiences of Black Americans. His thoughts and ideas appeared in weekly columns that were published in more than 100 newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s and appeared in several books including Race Adjustment (1908), Out of the House of Bondage (1914), and The Everlasting Stain (1924).

In addition to his duties as an educator and researcher, Miller served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Howard from 1907 to 1918. After spending over fifty years at Howard University as a student, teacher, and administrator, Miller retired from Howard in 1931. He died in Washington, D.C. on December 29, 1939, at the age of 76.

Kelly Miller’s influence and legacy went far beyond his work at Howard University, for over the years he became a national leader in the cause of the African-Americans.

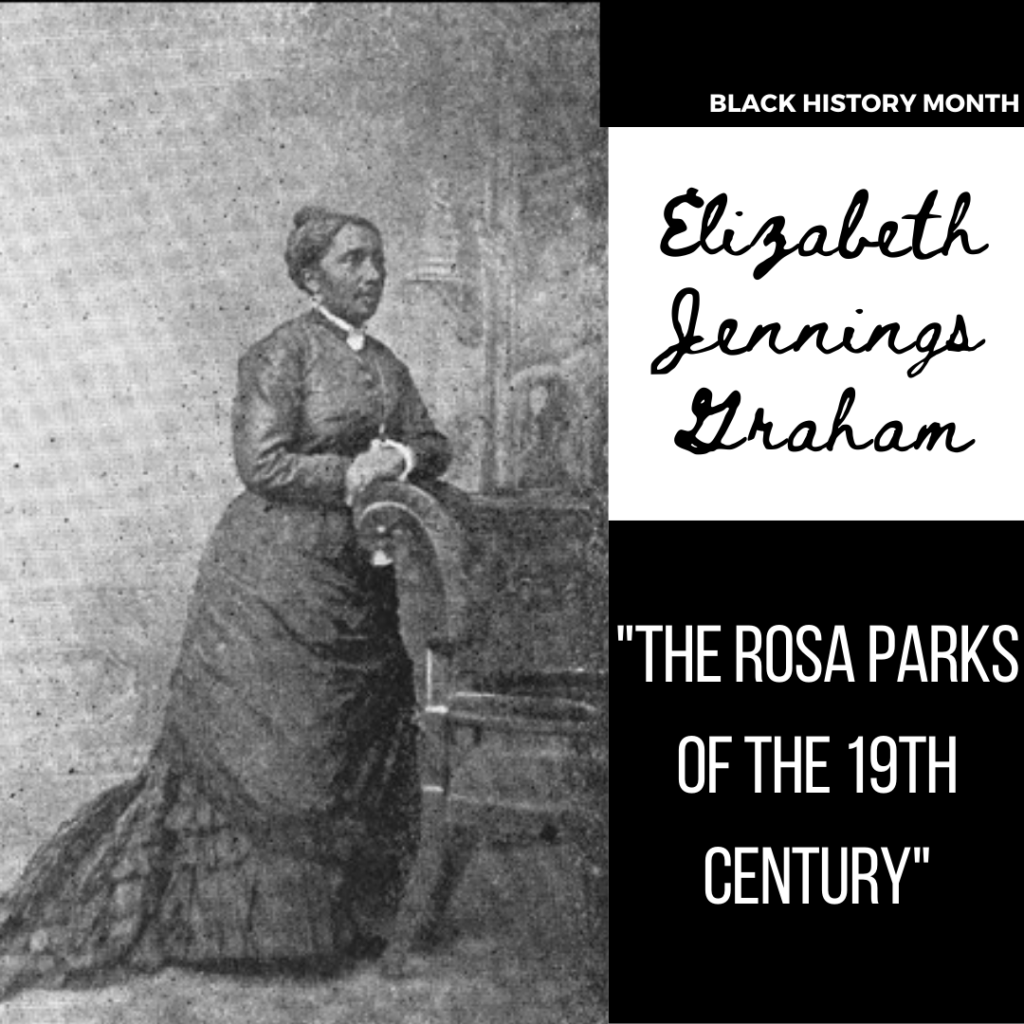

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (March 1827 – June 5, 1901) was an African-American teacher and civil rights activist, who challenged segregation on public transportation, a full 100 years before Rosa Parks did so. In 1854, she won a lawsuit against New York’s Third Avenue Railway Company for ejecting her from a streetcar because she was African American. The case led to the eventual desegregation of all New York City transit systems by 1865. She is known as “The Rosa Parks of the 19th Century”.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was born free in New York City to Thomas and Elizabeth Jennings in either 1826 or 1830 (both years are specific to her Death Certificate and 1850 Census, respectively). The specific day and month of her birth are unknown. Her parents were both prominent members of New York City’s small African-American middle class and her father was the first African American to hold a patent in the United States. Additionally, he was involved in many social and religious organizations and was one of the founders of New York’s Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Like her father, Graham was involved in many social and religious organizations, most prominently as a church organist. She, and her friend Sarah Adams, were on their way to the First Colored American Congregational Church on July 16, 1854, when she tried to board a streetcar of the Third Avenue Railway Company which at the time only allowed Euro-Americans as passengers. She was given permission to ride the streetcar, but the conductor told them, if any Euro-American passengers objected, “You shall go out or I’ll put you out.”

Jennings who wrote about the incident shortly after, said she told the conductor,

“I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York, did not know where he was born and that he was a good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.”

Replying that he was from Ireland, the conductor tried to haul Jennings from the car. She resisted ferociously, clinging first to a window frame, then to the conductor’s own coat. Continuing to drive, with Jennings’s companion left at the curb, he soon saw backup in the figure of a police officer, who boarded the car and pushed Jennings, her bonnet smashed and her dress soiled, to the sidewalk.

Graham’s forcible removal from the streetcar caused a massive protest against the streetcar company by members of New York’s African American community and others who felt she was unfairly treated. Her letter detailing the incident was read in church the next day; supporters forwarded the letter to The New York Daily Tribune, whose editor was the abolitionist Horace Greeley, and to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which both reprinted it in full. Meanwhile, her father hired an attorney and future 21st President Chester A. Arthur to sue the Third Avenue Railway Company on his daughter’s behalf. At the time, New York City and New York State had no laws regarding segregation on streetcars. Consequently, the court ruled that it had been illegal to forcibly evict Graham solely because she was African American, and awarded her $225 in damages. Her case itself did not lead to total desegregation of all streetcar lines, but it did set a precedent for future trials.

After the trial, Graham continued her career as a church organist and her career as a teacher. Later in life, Graham opened a kindergarten for African American children in her home. The kindergarten operated from 1895 until her death on June 5, 1901. Elizabeth Jennings Graham was buried in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery, along with her son and her husband.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was a pioneer in desegregation and education for African Americans in 19th century America. Her legacy lives on and continues to inspire.

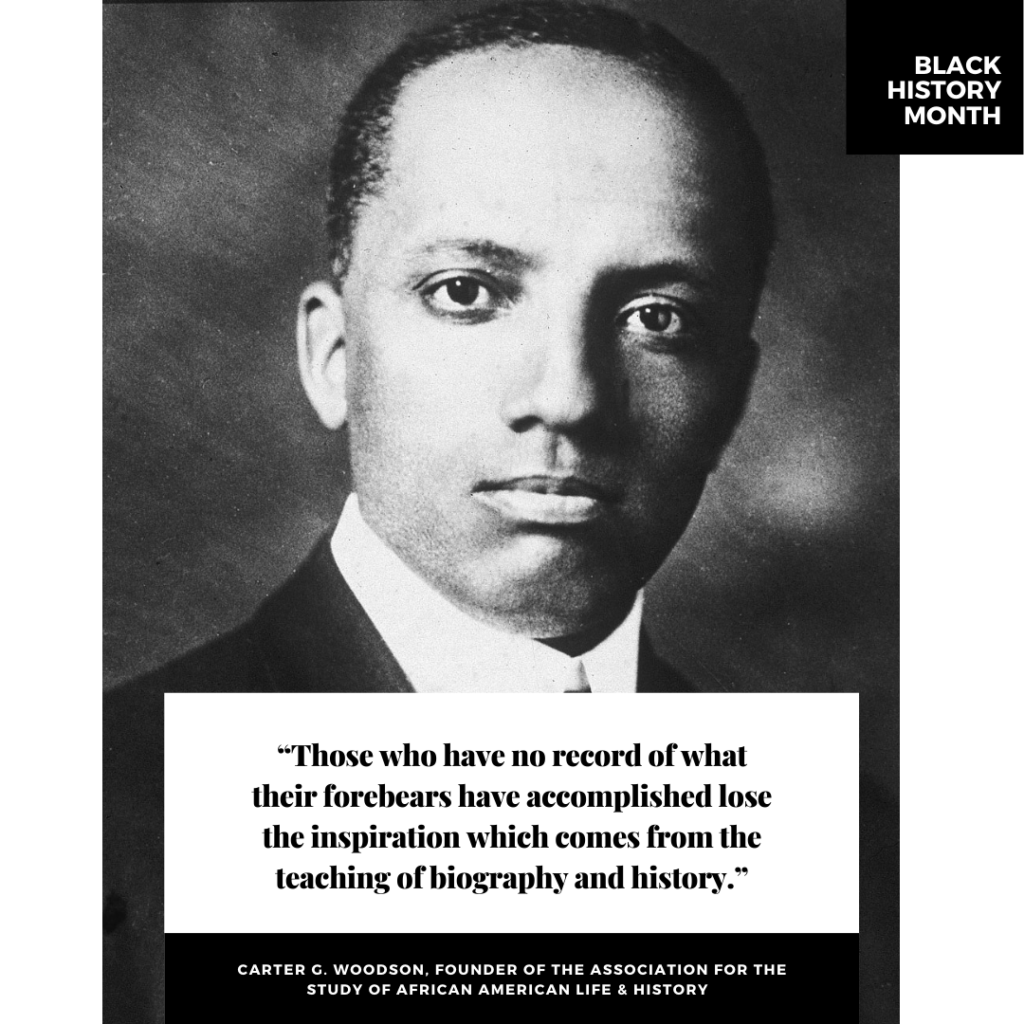

Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson, born December 19, 1875 in Virginia, was a distinguished Black historian, author, editor, publisher, and founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Additionally, as a founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the “father of black history” and in February 1926, launched the celebration of “Negro History Week”, which was the precursor to what we know and celebrate today as Black History Month.

Born the son of former slaves, both of whom could not read or write, Woodson helped his parents often on the family farm, thus unable to attend primary school. Regardless, he was able to master most of his school subjects through self-instruction by the age of seventeen.

Moving to Huntington, West Virginia in hopes to attend high school, he was forced to earn a living as a miner in the Fayette County coal fields while spending only a few months each year on his education. At the age of twenty, in the year 1895, Woodson entered Douglass High School, receiving his diploma in less than two years.

Woodson taught in Winona, Fayette County, from 1897 to 1900. In 1900, he returned to Huntington and became principal of Douglass High School, his alma mater. He also received his Bachelor of Literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1900. In the four years from 1903 to 1907, Woodson was a school supervisor in the Philippines. Post-Philippines, he traveled through Europe and Asia, studying at the Sorbonne University in Paris. He received his M.A. from the University of Chicago in 1908 and received his Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1912.

In 1915, Dr. Woodson and friends in Chicago established the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. The following year, 1916, the Journal of Negro History appeared, and in 1926, he developed Negro History Week, the

This is an excerpt from NAACP’s History Article on Dr. Carter G. Woodson:

“Dr. Woodson often said that he hoped the time would come when Negro History Week would be unnecessary; when all Americans would willingly recognize the contributions of Black Americans as a legitimate and integral part of the history of this country. Whether it’s called Black history, Negro history, Afro-American history, or African American history, his philosophy has made the study of Black history a legitimate and acceptable area of intellectual inquiry.“

Dr. Carter G. Woodson pioneered the celebration of “Negro History Week”, meant for the second week in February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. This idea continued with the Black United Students and Black Educators and Professors at Kent State University to include the entire month of February beginning in 1970.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson is among the thousands of Black Educators, Historians, Authors, Leaders, and Activists who made significant strides for equality and advancement of Black Americans.